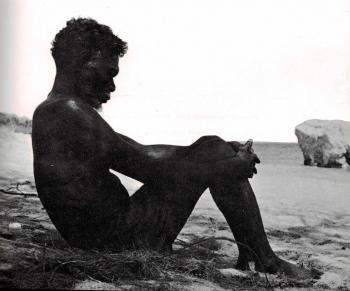

“Little Cracks of Their Own Mountain Ranges” : The Bark Petition, Church Panels, the Gove Land Rights Case The Formation of Aboriginal Australia’s First Title Deed

In pre-colonial Aboriginal Australia there was no legal title, no piece of paper kept in a safe spot to demonstrate legal ownership of a piece of land, as in Western law. The story of the Yirrkala Bark Petition is the story of how the Yolngu people of North East Arnhem land explained their land ownership and tenure, their responsibilities of land stewardship and of the family management of land (märi (MM/MB extended grandmother relations), gutharra (DD/ZD extended grandchild relations), yothu-yindi relations) over many generations.[1]

Fifty years later we can now partially see the marvellous system of stewardship, spiritual connection and ownership of lands that the Yolngu elders tried to explain to Australian politicians, courts and to the Australian people. In painting the church panels, and in framing the bark petition the Yolngu elders were indeed creating their own, and Australia’s first native title deed, indeed the Bark Petition has been described as Australia’s Magna Carta.[2] The Church Panels are a remarkable visual text and the references in the bark petition to the panels and Yolngu manikay (songs and ceremony) and law are of ongoing interest. As a nation and as a group of intellectually enlightened people there is a lot to say and analyse about the bark petition. It will remain something of interests to scholars and laymen alike for a long way into the future. Amongst other things, the Yolngu system allows us to partially conceptualise Aboriginal law and culture where languages have been lost and pre-colonial polity and society suppressed or lost.

Up until now, the bark petition has been seen as a kind of civil rights document in the thinking of our politicians. Fifty years on we see that it is the key to a remarkable and wise system of land tenure. The Church Panels are as much a document about flora and fauna should be managed as a document showing ownership. Land ownership comes with responsibilities. The deeply spiritual meanings of the panels and the petition, dismissed as not relevant to the common law by Justice Blackburn in the Gove Land Rights Case, are also worthy of major study and discussion. Non-Indigenous Australians can also learn a great deal from he concept of stewardship and management that is at the heart of the petition. This could, for example, be the basis for new sophisticated ideas for managing land and country, for passing responsibility for farms and land use on to future generations.

[1] The best book of explanation remains Nancy M. Williams, The Yolngu and their Land: A System of Land Tenure and the Fight for its Recognition, Stanford University Press, 1986. However the detailed interpretations of land ownership principles and meanings remain hot topics of conversation within Yolngu society itself.

[2] Will Stubbs, Director, Buku Larrngay Mulka, 9/7/2013

[1] The best book on this whole area remains Nancy M. Williams, The Yolngu and their Land: A System of Land Tenure and the Fight for its Recognition, Stanford University Press, 1986